If you’ve just happened across this piece, I would strongly urge you read Part 1 and meet all the wonderful people on the ground floor of Ranga Shankara, and then come back here.

If you’ve read Part 1, we left off at the foot of the staircase at Ranga Shankara. I walk up, and my first stop is the office on the mezzanine floor, where I meet Manjunath.

Manjunath has been at Ranga Shankara for the last three years, as an administrative manager. He laughs when I ask him how he started working at Ranga Shankara. “I saw the job posting on my friend’s sister’s WhatsApp Status, and I decided to apply.” From there, we began talking about the shows that he had watched. The first play he ever watched, which was after he joined Ranga Shankara was Karimayi, B. Jayashree’s long-running Kannada theatre production. “My job is to coordinate with everybody,” Manjunath says, “with local artists as well as Bombay and Delhi.

And inside Ranga Shankara also, I have to coordinate with technical staff, the interns, and everyone else.” I can’t imagine so many phone calls a day, but he reassures me that he enjoys the work of bringing it all together. “Everyone does everything here.” Manjunath adds. You get a sense of this when you come in to watch a play as well, that there is a certain warmth that the staff bring to the space. I was amazed to hear that Ranga Shankara was pretty much booked for the next six months – all the way till May, when this interview happened in November. Manjunath waved me into the theatre as his phone began ringing, and I padded into my favourite part of the space. Just in time to watch the lights being rigged for the day’s production.

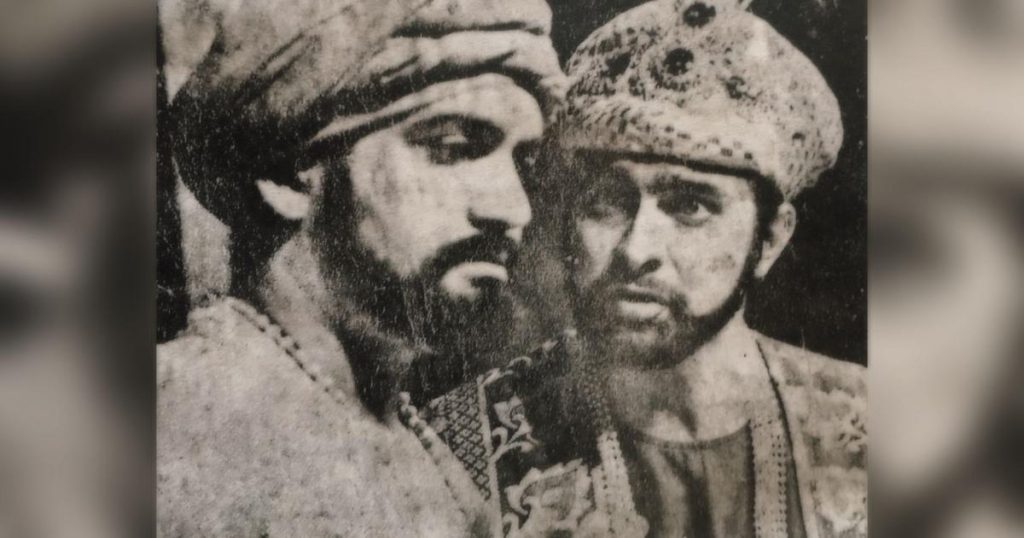

I sat on the soft benches watching the rigging, soaking in the smells and sights and chaos of technicians preparing for show day. As an actor who has performed here before, it is both familiar and utterly new to watch a show being set up, from the outside. And that’s the note on which my conversation with Prashanth sir and Murthy sir began. With twelve and fifteen years working at RS respectively, they are among the most experienced lighting operators in Bangalore. I asked them each to tell me about a project that they had worked on that was particularly memorable – Prashanth sir told me that every show was special in its own ways, and Murthy sir fondly talked about NeeNaaNaaDre NaaNeeNeNaa – a Sanket adaptation of Shakespeare’s A Comedy of Errors with over a hundred shows to its credit, helmed by multiple directors. We got talking about the joys of working with constraints, and this led to a discussion on how the dancers at Attakalari (a prestigious dance school based in Bangalore) use up to a whopping seventy lights and bring their own generator set, and other shows see anywhere between 25 and 50 lights. Set ups can begin the previous night for shows, and light technicians can find themselves working long hours leading up to performances. The most tender part of this conversation was when Prashanth sir and Murthy sir said that lighting and acting are (or should be) “two elements of a play that are constantly talking to each other, responding to one another in real time”. Of course, this is most obvious when new actors haven’t quite figured out how to catch the light, something they are irritated and amused by in equal measure. The next time you watch a play, and you suddenly see a light wash over the stage around a spot, you know that it was the lighting operator saving the actor and the day. I hope I haven’t ruined your watching experience. 🙂

As we joked around, the newest member of the lighting department joined us – Sachin. He has worked at Ranga Shankara for under a year, upon finishing his one-year diploma in performance at the Ninasam Institute (located in Heggodu, it is one of the oldest and most important theatre schools in Karnataka and perhaps the country). He compared lighting work to working as a doctor – diagnosing which light isn’t doing the job it’s supposed to and why, and so how to ‘treat it’ or rig it (to rig a light is to decide where in the theatre it should be placed, at what angle to the action on stage) so that its specific design purpose comes to light (pardon the pun) exactly as imagined. I liked this way of thinking about it.

This theme showed up again in my conversation with Muddanna. Thirty seconds into our conversation, he revealed to know that he worked backstage on the production of Girish Karnad’s Anju Mallige in 1978 (well, well before I was born!), another one of Sanket Trust’s seminal productions, featuring the acting talents of Anant Nag and others.

And then we segued into how much audiences have changed since the 70s and 80s, and how audiences in the last ten years seem to prefer to watch comedies. He reminisced about how social dramas, and other “serious” plays used to also run to packed houses forty years ago. I loved hearing about how he would travel with troupes to all kinds of locations and rig lights with bamboo sticks and ropes, with someone particularly agile climbing the rickety structure. “Now these rigs can be moved with the flick of a switch”, rues Muddanna, “It’s a convenience but we have lost some of the energy and enthusiasm that came with overcoming such challenges.”

It was so evident that Muddanna sir has been watching this space change, and that his observations are living testimony to the ways theatre making was and is shifting. It really brought home the point that people are our greatest resource, both for people in the theatre and outside, and that most of us don’t realise how much a conversation like this can add to our perspective on what next.

Anyway, back to the task at hand.

The final person I wanted to speak to was elusive. Flitting around floor to floor with not a moment of rest, was Sujith, the housekeeping supervisor. He manages a small and dedicated housekeeping team that carries the behemoth that is Ranga Shankara. He told me about all the jobs he had done before he became supervisor – having seen difficulties and joys alike. We talked briefly about annual day school productions (a treasured part of both our childhoods). When I asked him to tell me about a play that he enjoyed recently, he told me about the Tamil play Patigalum (by the Chennai troupe Thinnai Nilavaasigal, staged recently at the Ranga Shankara Theatre Festival 2023) What did he like about it? “I liked that they talked about things no one wants to say.”

He also said something so revealing to me right after – about how the success of the housekeeping staff was measured by how little other people noticed them. “People only think about us when things go wrong,” Sujith says, “so if no one says anything, that’s good!” I was struck by this remark, by the hours of physical labour that is never seen in places that run smoothly. When I ask Sujit for a picture, he is shy. “No one has asked me questions like this – about the plays” he tells me with a smile before he leaves to his next set of invisible tasks.

These few hours I spent in Ranga Shankara preparing for this essay have been completely unlike any of the hundreds of hours I’ve spent there before. What a rare gift to arrive again at a space you thought so familiar all your life, and to see it completely anew!

I invite you to say hello to all the space-holders who keep this theatre running when you’re at Ranga Shankara next (which I hope is sooner rather than later). To say hello is to really see the space, to make visible the people who work tirelessly to make the theatre about the experience, and not just the show.