The show must go on!

Must it, really? Why, and at what cost?

Last month a dancer friend recalled how she had hurt her right leg at rehearsals a day before her show premiered. “I shouldn’t have performed, but there was no question of cancelling. The show went off well, but I had aggravated the injury to a point where I needed a major surgery.” Needless to say, there was no medical insurance, no financial support either for her surgery or while she was recovering.

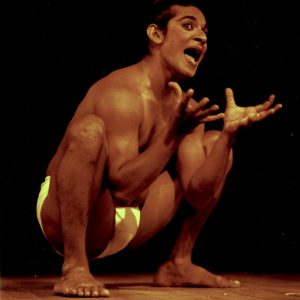

This is not an unusual story in the world of performing arts I could bet that every performer you know could regale you with at least one story of how they performed with a burning fever, or took steroid shots just to be able to get through a performance or how they used cello tape to bind a bleeding wound for a show. It’s not unheard of for artists to put themselves at risk rather than cancel a show. It’s almost as if we’re primed for this, because the alternative – cancelling a show – is blasphemous. And so the stories continue: from the innocuous “I had a broken toe-nail” to the scary “The floor was slippery with blood, but I kept going till the curtains came down before passing out.” Stories we’ve heard far too many times without questioning why these shows had to go on.

Actually, what’s the worst that could happen if the audience was offered an explanation and a refund? Surely none of us believe that there would be blood on the streets because of a cancelled performance. Imagine the headlines: ‘Riots in Bangalore: Angry theatre lovers clash on the streets due to cancelled shows at Ranga Shankara’.

Now that might even be a world worth living in.

Remember Freddy Mercury singing The show must go on? Queen recorded it in 1990; Mercury, the lead singer died the following year. When he recorded the song, he, and his bandmates knew he was going to die soon. And yet, it was important that he hide his physical and mental agony from the world. Listen to the lyrics carefully, it feels like he’s breaking inside:

The show must go on

Inside my heart is breaking

My make-up may be flaking

But my smile, still, stays on.

Heart breaking, and therefore begging the million-dollar question, why?

There’s really no consensus on the origin of the phrase – The show must go on. Some believe that Shakespeare’s Henry IV hinted at it with, “Play out the play”. Most others agree that the phrase originated from the circus sometime in the 19th century. According to James Rogers in The Dictionary of Cliches, “If an animal escaped or a performer was injured, the ringmaster and the band were expected to keep things going, so the crowd would not panic.” Imagine that! A lion or tiger is on the prowl, and the performers on stage continue playing, and smiling, pretending that all’s well!

“I’ve never believed in the adage – the show must go on,” says theatre performer, director and teacher Mallika Prasad. But, Mallika, unbeknownst to her, was the heroine of a theatre legend in Bangalore 20 years ago. Athol Fugard’s Road to Mecca performed in Delhi with Mallika allegedly on a wheelchair, thanks to a broken leg. “Foot, not leg, but I had a blue fibreglass cast – game changer that, because I could hobble around. We were to travel by train to Delhi, imagine the fomo if I missed that,” she laughs while clarifying that she did not perform on a wheelchair.

Newbies in the theatre are often told these inspiring stories of personal sacrifices and hardships endured by seniors in their heydays. 15 years ago, it sounded heroic, today it feels downright irresponsible and manipulative. Do we tell these stories to prepare actors to bind their legs with cello tape in case of injury instead of seeking help. What if, instead, we told newcomers stories of care and compassion, about how we cancelled shows because team members were injured, and how we took time to help each other. Maybe stories about taking turns at the hospital, raising money for team mates, helping them recover. Heroism of another kind, perhaps.

I remember stories of performers on tour opting to complete shows even on hearing of a parent’s death. “Just before the show Vinay (Kumar) heard that his father had passed away, the organisers gave him the option to leave, they were ready to cancel the show, but Vinay took some time, I remember him pacing up and down, and finally decided to do the show,” remembers Nimmy Raphael of Adishakti’s performance of Brhannala at Edinburgh. Then there were actors who returned to the theatre straight after the funeral of a parent or sibling for scheduled shows. What is this pressure we put ourselves through and why are we not assessing the long term psychological and emotional impact of these incidents. I remember Atul Kumar of The Company Theatre, Mumbai telling me about how Sheeba Chaddha (who incidentally is rocking the award season for her film work) bled from her head during a show of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, because something had fallen on her head backstage, yet, she continued to perform with blood dripping from under her hat. “Yes, it happened,” Sheeba recalls.

The show must go on means that our physical and mental agony doesn’t matter, that it is secondary to what happens on stage – the show that we put on for an audience. It seems about time we changed the narrative a bit. We could perhaps start by choosing better stories to tell. I leave you with Hannah Gadsby who says, “Do you know why we have The Sunflowers? It’s not because Vincent van Gogh suffered. It’s because van Gogh had a brother who loved him. Through all the pain, he had a tether, a connection to the world. And that is the focus of the story we need -connection.” And for all of us who love the theatre, maybe these are the new stories we need to tell.